Jesus Used the Story of in the Old Testament to Tell About Being Buried and Living Again

The burial of Jesus refers to the burying of the trunk of Jesus after crucifixion, before the eve of the sabbath described in the New Testament. Co-ordinate to the approved gospel accounts, he was placed in a tomb by a councillor of the sanhedrin named Joseph of Arimathea,[2]. In art, information technology is often called the Entombment of Christ.

Biblical accounts [edit]

The earliest reference to the burial of Jesus is in a letter of Paul. Writing to the Corinthians effectually the twelvemonth 54 AD,[3] he refers to the business relationship he had received of the death and resurrection of Jesus ("and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third twenty-four hours co-ordinate to the Scriptures").[4]

The four canonical gospels, written between 66 and 95, all conclude with an extended narrative of Jesus' abort, trial, crucifixion, burial, and resurrection.[5] : p.91 All four state that, on the evening of the Crucifixion, Joseph of Arimathea asked Pilate for the body, and, later on Pilate granted his request, he wrapped it in a linen fabric and laid it in a tomb.

Modern scholarship emphasizes contrasting the gospel accounts, and finds the Marking portrayal more probable.[6] [seven]

Gospel of Marker [edit]

In the Gospel of Mark (the primeval of the canonical gospels), written effectually the years 50 to 70,[8] [ix] Joseph of Arimathea is a member of the Jewish Council – the Sanhedrin which had condemned Jesus – who wishes to ensure that the corpse is buried in accordance with Jewish law, according to which dead bodies could not be left exposed overnight. He puts the body in a new shroud and lays it in a tomb carved into the stone.[six] The Jewish historian Josephus, writing afterwards in the century, described how the Jews regarded this law as so important that even the bodies of crucified criminals would exist taken downwardly and cached before sunset.[10] In this account, Joseph does simply the bare minimum needed for observance of the police force, wrapping the body in a cloth, with no mention of washing or anointing it. This may explain why Marker mentions an consequence prior to the crucifixion in which a woman pours perfume over Jesus.[11] Jesus is thereby prepared for burial even before his expiry.[12]

Gospel of Matthew [edit]

The Gospel of Matthew was written around the years 50 to 70, presumably using the Gospel of Marker as a source.[xiii] In this business relationship Joseph of Arimathea is non referenced as a fellow member of the Sanhedrin, just a wealthy disciple of Jesus.[14] [fifteen] Many interpreters have read this as a subtle orientation by the author towards wealthy supporters,[15] while others believe this is a fulfillment of prophecy from Isaiah 53:9:

"And they fabricated his grave with the wicked, And with the rich his tomb; Although he had done no violence, Neither was whatever deceit in his oral cavity."

This version suggests a more honourable burial: Joseph wraps the body in a clean shroud and places it in his own tomb, and the word used is soma (torso) rather than ptoma (corpse).[16] The author adds that the Roman authorities "fabricated the tomb secure by putting a seal on the stone and posting the guard."

Gospel of Luke [edit]

The Gospel of Mark is as well a source for the account given in the Gospel of Luke, written around the year 60-61.[17] As in the Markan version, Joseph is described equally a fellow member of the Sanhedrin,[18] but as not having agreed with the Sanhedrin's determination regarding Jesus; he is said to have been "waiting for the kingdom of God" rather than a disciple of Jesus.[19]

Gospel of John [edit]

The Gospel of John, the concluding of the gospels, was written around the years eighty to 90, and it depicts Joseph as a disciple who gives Jesus an honourable burial. John says that Joseph was assisted in the burial procedure by Nicodemus, who brought a mixture of myrrh and aloes and included these spices in the burial textile according to Jewish customs.[20]

Comparison [edit]

The comparison below is based on the New International Version.

| Matthew | Marking | Luke | John | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joseph and Pilate | Matthew 27:57–58

| Mark 15:42–45

| Luke 23:50–52

| John 19:38

|

| Burial | Matthew 27:59–61

| Marking xv:46–47

| Luke 23:53–56

| John 19:39–42

|

| Loftier priests and Pilate | Matthew 27:62–66

| |||

| Mary(s) | Matthew 28:ane

| Mark sixteen:one–two

| Luke 24:1

| John 20:1

|

In non-canonical literature [edit]

The apocryphal manuscript known as the Gospel of Peter states that the Jews handed over the torso of Jesus to Joseph, who after washes him then buries him in a identify called "Joseph's Garden".[23]

Historicity [edit]

Due north. T. Wright notes that the burial of Christ is office of the earliest gospel traditions.[24] John A.T. Robinson states that the burying of Jesus in the tomb is ane of the earliest and best-attested facts well-nigh Jesus."[25] Rudolf Bultmann described the basic story as 'a historical account which creates no impression of being a fable'.[26] Jodi Magness has argued that the Gospel accounts describing Jesus's removal from the cross and burial accordance well with archaeological bear witness and with Jewish law.[27]

John Dominic Crossan, however, speculates that Jesus' body may have been thrown into a shallow grave and eaten by dogs, the bones scattered.[28] Martin Hengel and Maurice Casey argued that Jesus was cached in disgrace as an executed criminal who died a shameful decease, a view debated in scholarly literature.[29] [30] Bart D. Ehrman initially stated that Jesus was cached by Joseph of Arimathea,[31] but subsequently changed his mind and stated that Jesus was probably thrown into a common grave for criminals.[32]

Theological significance [edit]

Paul the Apostle includes the burial in his argument of the gospel in verses 3 and 4 of 1 Corinthians xv: "For I delivered unto you lot kickoff of all that which I likewise received, how that Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures; And that he was cached, and that he rose once again the 3rd day according to the scriptures" (KJV). This appears to be an early on pre-Pauline credal statement.[33]

The burial of Christ is specifically mentioned in the Apostles' Creed, where it says that Jesus was "crucified, dead, and cached." The Heidelberg Canon asks "Why was he cached?" and gives the answer "His burial testified that He had really died."[34]

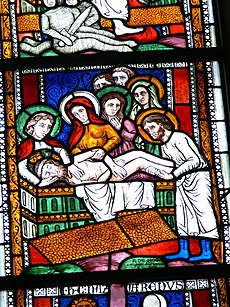

A 13th century version of the Entombment of Christ in stained-drinking glass

The Catechism of the Cosmic Church building states that, "It is the mystery of Holy Saturday, when Christ, lying in the tomb, reveals God's slap-up sabbath remainder after the fulfillment of human's salvation, which brings peace to the whole universe" and that "Christ's stay in the tomb constitutes the real link between his passible state before Easter and his glorious and risen state today."[35]

Depiction in fine art [edit]

The Entombment of Christ has been a pop subject in art, being developed in Western Europe in the 10th century. It appears in cycles of the Life of Christ, where it follows the Deposition of Christ or the Lamentation of Christ. Since the Renaissance, it has sometimes been combined or conflated with 1 of these.[36]

Wooden sculpture of Christ in His tomb past anonymous

Notable individual works with articles include:

- The Entombment (Bouts, c. 1450s)

- Lamentation of Christ (Rogier van der Weyden, c. 1460-1463)

- The Entombment (Michelangelo, c. 1500-01)

- The Deposition (Raphael, 1507)

- The Entombment (Titian, 1525)

- The Entombment (Titian, 1559)

- The Entombment of Christ (Caravaggio, 1603-04)

- Veiled Christ (Sanmartino, 1753)

Use in hymnody [edit]

The African-American spiritual Were y'all there? has the line "Were yous there when they laid Him in the tomb?"[37] while the Christmas ballad We Three Kings includes the verse:

Myrrh is mine, its bitter perfume

Breathes a life of gathering gloom;

Sorrowing, sighing, bleeding, dying,

Sealed in the stone cold tomb.

John Wilbur Chapman's hymn "One Mean solar day" interprets the burying of Christ by maxim "Buried, He carried my sins far abroad."[38]

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the post-obit troparion is sung on Holy Saturday:

The noble Joseph,

when he had taken down Thy near pure torso from the tree,

wrapped it in fine linen and anointed information technology with spices,

and placed information technology in a new tomb.

Creative depictions [edit]

-

Entombment of Christ, 15th century, Belgium

-

See besides [edit]

- Tomb of Jesus, multiple sites purported to be Christ's burial place

- Descent from the Cross

- Empty tomb

- Epitaphios (liturgy)

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- Harrowing of Hell

References [edit]

- ^ "The Entombment of Christ (1601-3) by Caravaggio". Encyclopaedia of Arts Education. Visual Arts Cork. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ Kaitholil. com, Inside the church of the holy sepulchre in Jerusalem, archived from the original on 2019-08-nineteen, retrieved 2018-12-28

- ^ Watson E. Mills, Acts and Pauline Writings, Mercer Academy Printing 1997, page 175.

- ^ 1COR xv:iii-4

- ^ Powell, Marking A. Introducing the New Testament. Bakery Bookish, 2009. ISBN 978-0-8010-2868-vii

- ^ a b Douglas R. A. Hare, Marking (Westminster John Knox Press, 1996) page 220.

- ^ Maurice Casey, Jesus of Nazareth: An Contained Historian'due south Account of His Life and Didactics (Continuum, 2010) folio 449.

- ^ Witherington (2001), p. 31: 'from 66 to 70, and probably closer to the latter' sfnp error: no target: CITEREFWitherington2001 (help)

- ^ Hooker (1991), p. viii: 'the Gospel is usually dated between AD 65 and 75.' sfnp error: no target: CITEREFHooker1991 (help)

- ^ James F. McGrath, "Burial of Jesus. Ii. Christianity. B. Modernistic Europe and America" in The Encyclopedia of the Bible and Its Reception. Vol.4, ed. by Dale C. Allison Jr., Volker Leppin, Choon-Leong Seow, Hermann Spieckermann, Barry Dov Walfish, and Eric Ziolkowski, (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2012), p. 923

- ^ (Mark 14:3–9)

- ^ McGrath, 2012, p.937

- ^ Harrington (1991), p. 8. sfnp error: no target: CITEREFHarrington1991 (help)

- ^ Daniel J. Harrington, The Gospel of Matthew (Liturgical Press, 1991) page 406.

- ^ a b Donald Senior, The Passion of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew (Liturgical Press, 1990) page 151.

- ^ Donald Senior, The Passion of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew (Liturgical Printing, 1990) page 151-2.

- ^ Davies (2004), p. xii. sfnp error: no target: CITEREFDavies2004 (help)

- ^ N. T. Wright, Luke For Everyone (Westminster John Knox Press), page 286.

- ^ Luke 23:fifty–55

- ^ John xix:39–42

- ^ It's non articulate whether 'the Quango' (τῇ βουλῇ) refers to the Sanhedrin (τὸ συνέδριον, Luke 22:66), but it'southward likely.

- ^ a b Going by Matthew 27:56, this was Mary, the female parent of James and Joseph.

- ^ Walter Richard (1894). The Gospel Co-ordinate to Peter: A Written report. Longmans, Dark-green. p. 8. Retrieved 2022-04-02 .

- ^ Wright, Due north. T. (2009). The Challenge of Easter. p. 22.

- ^ Robinson, John A.T. (1973). The human face of God . Philadelphia: Westminster Press. p. 131. ISBN978-0-664-20970-iv.

- ^ Magness, Jodi (2011). Stone and Dung, Oil and Spit: Jewish Daily Life in the Time of Jesus. Eerdmans. p. 146.

- ^ Magness, Jodi (2005). "Ossuaries and the Burials of Jesus and James". Periodical of Biblical Literature. 124 (1): 121–154. doi:ten.2307/30040993. ISSN 0021-9231. JSTOR 30040993.

- ^ Crossan, John Dominic (2009). Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography. p. 143.

- ^ Hengel, Martin (1977). Crucifixion in the Ancient World and the Folly of the Bulletin of the Cantankerous. Fortress Press. ISBN978-0-8006-1268-9.

- ^ Casey, Maurice (2010-12-30). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching. A&C Black. p. 448. ISBN978-0-567-64517-3.

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (1999). Jesus, apocalyptic prophet of the new millennium. Internet Archive. Oxford Academy Press. ISBN978-0-19-512473-half-dozen.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (2014-03-25). How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee. Harper Collins. ISBN978-0-06-225219-7.

- ^ Hans Conzelmann, 1 Corinthians, translated James Westward. Leitch (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1969), 251.

- ^ Heidelberg Canon Archived 2016-10-17 at the Wayback Machine, Q & A 41.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 624-625 Archived December 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ G Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. Ii,1972 (English language trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, p.164 ff, ISBN 0-85331-324-5

- ^ "Cyberhymnal: Were You There?". Archived from the original on October 7, 2011.

- ^ "Cyberhymnal: One Day". Archived from the original on September 24, 2011.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burial_of_Jesus

0 Response to "Jesus Used the Story of in the Old Testament to Tell About Being Buried and Living Again"

Post a Comment